More Information

Submitted: May 22, 2023 | Approved: June 15, 2023 | Published: June 16, 2023

How to cite this article: Farzana F, Sarwar T. Perceptions of Adolescent Mothers on Feeding and Nutrition of their Children aged 0-3 Years in Rural Bangladesh. Arch Food Nutr Sci. 2023; 7: 054-064.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.afns.1001050

Copyright License: © 2023 Farzana F, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: In Rural Bangladesh; Adolescent mothers; Infant; Young children; Exclusive breastfeeding; Complementary feeding

Perceptions of Adolescent Mothers on Feeding and Nutrition of their Children aged 0-3 Years in Rural Bangladesh

Faiza Farzana1* and Tanvir Sarwar2

1Department of Early Childhood Development, BRAC University, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh

2Department of Applied Nutrition and Food Technology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Islamic University, Kushtia-7003, Bangladesh

*Address for Correspondence: Faiza Farzana, Department of Early Childhood Development, BRAC University, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh, Email: [email protected]

Proper feeding practices at an early age are the key to improving a child’s overall health and achieving developmental milestones. In Bangladesh, a large portion of rural girls become mothers before the age of 18. Past records show that most interventions are designed to improve infant and young child feeding practices targeting older mothers. That is why, this study has been designed with an aim to explore the perceptions and practices of infant and young children feeding among rural Bangladeshi mothers aged < 19 years old. Data was collected through in-depth interviews and group discussions with a total of 40 adolescent mothers who have children aged 0-3 years. Data has revealed that the majority of the mothers hold very limited knowledge of nutrition and child nutrition but those who are educationally a bit ahead hold a little better knowledge. Participants are aware of breastfeeding but they all misinterpret the term ‘exclusive breastfeeding’ with other liquid food. It has also emerged that most of the mothers know the ideal timing of starting complementary feeding but very few of them actually understand what to feed children. In spite of having misconceptions and superstation rural adolescent mothers practice responsive feeding instead of force-feeding. No gender discrimination has been found regarding child feeding. The findings of the study pinpointed that mothers are unable to practice proper infant and child feeding due to a lack of knowledge and limited affordability. Educating girls & young mothers and improving financial security could be an effective way to promote improved infant feeding practices.

Proper nutrition and appropriate feeding during the earliest stages are basic to guarantee early childhood as well as the further development, well-being, and advancement of children to achieve their potential. The very first years of human life provide an essential way of amenities for guaranteeing children’s suitable development and improvement by perfect feeding practices. To improve the overall situation of a nation, improving the newborn children’s and young children’s nutritional status is a mandatory need for the whole human development. The physical and mental well-being of children can be hampered by destitute nutrition amid early years which subsequently may lead to a more prominent chance of casualty from communicable infections or extra critical contaminations which eventually end in a greater financial ‘burden on society [1,2].

From previous recommendations, it has been found that mothers’ education is strongly related to the convenient introduction of family food as well as complementary feeding and other issues. Meal frequency, dietary diversity, and the practice of a least acceptable diet are the ‘other issues that are related to mothers’ knowledge [3]. Additionally, the socio-economic background of the family, introduction to media like television or other media, maternal age, geographical area, and the utilization of antenatal and postnatal visits are related to progressing complementary feeding practices [4]. A study uncovered that mothers had a higher chance of not introducing complementary foods timely if they had no education [5]. As mostly the primary caregiver of a child is his/her mother if the mother does not have ideas about child feeding and nutrition children might be fed unhygienic and improper nourishment even before completing 6 months and also further transition of feeding would not be designed in the proper way. If the mother fails to design the proper meal, it indicates a child’s poor nutrition that will hamper his/her development, and improvement and contributes significantly to child malnutrition. A child’s regular dietary intake can have an incredible effect on her/his development and advancement [6]. As mothers are the main provider of food, mothers’ perceptions of nutrition could play an imperative part in a child’s feeding and nutrition to progress wholesome status.

From past studies, it has been seen that all over the world breastfeeding is still poor, and complementary feeding practices are way far to reach. From past records of WHO, around the world, it is assessed that just 34.8% of newborn children are solely breastfed for the first 6 months of their life, the larger part getting a few other foods or liquids within the early months [7]. Information from 64 nations covering 69% of births within the developing countries recommend that there have been advancements in this circumstance. In securing appropriate nutrition according to the age of young children, which is basic and foremost for avoiding undernutrition during early development, Bangladesh faces a few challenges. According to the report of WHO (2020), in Bangladesh, only 33 percent of children are given complementary foods at the right time with convenient design, and only 23 percent of children are fed according to the recommendations of infant and young child feeding practices. A study has found that rural infants are more likely to reach the amount of problematic complementary feeding practices as compared to children from urban areas [8]. Another study revealed that more scientific feeding practice was found in urban respondents than in rural ones due to education variables. The nutritional status of the chosen newborn children was found to be varied with varying degrees, but an improved dietary condition was found in urban newborn children than in rural ones [9].

To ensure the holistic development of a child, it is essential to emphasize the practices of appropriate complementary food from a dietary standpoint according to a distinctive age group. Although Bangladesh includes a strong culture of breastfeeding, suitable feeding practice is still very low. Mothers are often unaware that they are able to feed their children nutritionally satisfactory, effectively prepared, cost-viable homemade complementary food. A study has pinpointed that mothers’ knowledge of IYCF suggestions has been associated with IYCF practices of theirs. Mothers who are having inadequate, poor knowledge of IYCF recommendations are more likely to have improper IYCF practices [10,11]. A few variables influence mothers’ knowledge of IYCF recommendations. These variables are corporate with mothers’ working status, educational status, family estimate, the conjugal situation of the mother, and the age and sex of the child (Central Statistical Agency and ICF International, 2012) [12]. Although the reality is that, universally, between 14 and 15 million juvenile young ladies aged 15 to 19 years old allow birth each year but sadly most of the past research on IYCF has targeted adult women. (Krishty, 2007). Bangladesh has a higher rate of child marriage which is approximately 51% and rural girls are giving birth before reaching the age of 18 and completing their studies [13]. Some previous research in Bangladesh had done to investigate what are the complexities of newborn child-feeding practices among older Bangladeshi mothers [14-18]. For this context, this study has been designed with the goal to measure IYCF perceptions among rural adolescent mothers and to explore their practices related to destitute IYCF practices. Improved and appropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices are important, if we need to develop both physical and mental prosperity and advancement of young children, unfortunately in Bangladesh, research on perceptions and practices of adolescent mothers on feeding and nutrition is limited. Most intercessions and interventions are designed to target the improvement of IYCF practices among older mothers [19]. This study would contribute to the knowledge creation on the perceptions and practices of adolescent mothers in this regard.

From the statistics of UNICEF [13], it is found that adolescent mothers are more likely to drop out of school and eventually cannot complete their education, also they have a low chance of future employment opportunities. Mothers’ less education might indicate that they do not have proper knowledge of the health and well-being of their children. Without knowing the perceptions of adolescent mothers, we might not be able to understand where the knowledge gap exists. We may not be able to design an effective intervention or advocacy program for them. It is important to document the adolescent mothers’ perceptions for further research. The findings of the study are expected to offer assistance to the individuals who are responsible for making policies. Thus policymakers would be able to target strategies like ‘alteration of behavior’ in mothers to upgrade the IYCF practices in rural Bangladesh.

Research objectives

The two main objectives of this study are mentioned below:

- To explore adolescent mothers’ perceptions regarding feeding and nutrition of their children aged 0-3 years in rural Bangladesh

- To explore adolescent mothers’ feeding and nutrition practices in the regular life of their children aged 0-3 years.

Research questions

R.Q 1: What is the understanding of adolescent mothers’ regarding nutrition and feeding of their children aged 0-3 years?

R.Q2: How adolescent mothers are practicing child feeding in terms of dietary intake and adequacy in the regular life of their children aged 0-3 years?

Research approach

To explore mothers’ perceptions and practices towards infant and young child feeding and nutrition, a qualitative approach was followed. As the researcher was interested in obtaining information regarding mothers’ perceptions towards nutrition, child nutrition, child feeding, and mothers’ practice on child feeding qualitative design was employed. As qualitative research means “any kind of research that produces findings not arrived at by means of a statistical procedure or other means of quantification” (Strauss & Corbin, 1991, p.17)-it seemed most appropriate therefore to employ a qualitative approach to the research. One of the aims of my study was to find out the perceptions of mothers towards child feeding and nutrition; what they know, what are their concepts on feeding and nutrition and also to find out mothers’ practice on child feeding; how they practice child feeding in their regular life which is also a reason of designing qualitative study. According to Polit & Beck (2010), the goal of most qualitative studies is not to generalize because the focus is on the local, the personal, and the subject. To fulfill the requirement of the study in-depth interviews and group discussions were conducted.

Study setting

The data was collected from two villages of two upazilas of Faridpur District, which is 158 kilometers far away from the Capital City Dhaka. Two different villages from the same district were selected because they are mostly similar socially and culturally.

Study participants

The target population was the rural adolescent mothers aged between 15-18 years and having child/children 0-3 years old. Though primarily 11-18-year-old mothers were designed as the target population but while doing data collection only 15-18 years old mothers were available. The mothers who were more than 18 years old and lived in urban areas were excluded. Mothers who do not have children aged between 0 to 3 years were also excluded. Additional exclusion criteria were mental disability, visible sickness or not comfortably participating for the duration and question of the interview.

Research participants

There were 40 participants in total, 20 from each village. 20 participants were asked for an in-depth interview and another 20 participants participated in group discussion. Data was also collected on age, education, family form, and family income.

Participants selection procedure

In this study, the participant selection process was purposive. Adolescent mothers who have child/children aged between 0 to 3 years living in the Faridpur district were the inclusion criteria.

Research instruments

In-depth interviews and informal group discussion guidelines were used as data collection tools for the study. The guidelines were developed by the researcher and were reviewed by the experts.

Data collection procedure

The data collection was started after developing and reviewing the In-depth Interview (IDI) and group discussion guidelines of the experts. After conducting 2 piloting of the tools with 2 participants the guidelines were revised more than once through the required revision for more accuracy and to make the data collection more fruitful. A total of 20 IDIs and 4 group discussions in the two different rural areas of the Faridpur district were conducted. The areas are respectively Sadarpur and Shovarampur.

To conduct the IDIs with the mothers coming from a low-middle income background in rural areas, oral consent was taken from the adolescent mothers as per their preferences. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews maintaining all the necessary health protocols. If they wanted to skip any question then the specific questions listed in the guidelines were not asked. All the data were documented descriptively through field notes and tape recorders. Two IDIs were conducted in a day and the length of each IDI was 60-90 minutes. The IDI guideline contained semi-structured questionnaires. The responses were primarily recorded with audiotape and then it was transcribed. Four group discussions with a total of 20 mothers (10 mothers from each upazila) were conducted. One group discussion was conducted on the same day. The length of each group discussion was 60 to 90 minutes. Group discussion guideline was developed and designed by the researcher herself using easy-understanding language. Mother’s knowledge and attitudes towards nutrition and feeding and the practices concerns with everything were covered in the group discussion questionnaire in a semi-structured manner.

Data management and analysis

In-depth interviews & group discussions were conducted for this study and data was overseen from the beginning of the data collection method. While taking the In-depth interviews and group discussions each participant`s comments, their reflections everything was recorded. Each day after talking to the participant every note was reorganized with date and time. Without any further delay, it was precisely put on papers for the transcriptions. During memoizing the transcript, all indicating impressions of the participants were recorded, and the main data which was significant to research questions and sub-questions were organized and highlighted. For this study, researchers utilized the concept of content analysis. According to Holsti (1968) “content analysis is any procedure for making inductions by systematically and objectively distinguishing indicated characteristics of messages” [20]. Another reason for using a content analysis strategy was as it includes classifying and coding information with the goal of making the collected data sensible and highlighting the imperative key messages, forms, and findings. Then categorizing thematic design was done based on the collected data. In qualitative research, the most common form of analyzing the data is thematic analysis. According to some researchers it is stated that, for identifying, analyzing, and documenting trends (themes) within the data, thematic analysis is the tool that is used [21]. Finally, the findings of the study are displayed distinctly under each theme and translated and displayed according to them.

Reliability and validity

The researcher took absolute care in conducting the study. As legitimacy is an issue in qualitative research to protect the precision and validity of the study, a few methodologies were maintained to guarantee the validity of this study. To ensure credibility, peer debriefing was done with a mentor. Member checking was conducted with one research participant. The researcher perused a few pieces of information from the transcript to check the precision and meaning of the chosen participants. In order to guarantee transferability, nitty gritty clear data were collected. Suitable strategies were maintained based on the research objectives and questions and guidelines for in-depth interviews and group discussions in conjunction with the deciphered version were checked and reviewed by experts. For conformability and reflexivity practice reflective journals were also kept. The reliability of the study was maintained by defining the questionnaire clearly. Simple and clear dialect was used, checked, and reviewed by experts, and based on their feedback, in- depth-interview, and group discussion guidelines were edited more than once. Field testing was also conducted with two mothers before the main data collection.

Ethical issue

All ethical issues related to research involving human subjects are addressed according to the Ethical approval committee of IED, BRAC University. The prospective participants were given a free opportunity to receive summary information of the study including purpose in writing before giving consent and taking part in the interview. Confidentiality of the participants was strictly maintained and no name of the respondents was analyzed. The ethical issue considered the following things:

- Voluntary participation: Participants agreed to participate in this study voluntarily. Informed consent: Participants of the study were informed about the procedure and risks involved in participating in the study and based on that information, participants made an independent voluntary decision to give their consent to participate.

- Confidentiality: During this study, the researcher gave assurance to the participants that identifying information obtained about them would not be released to anyone outside the study. The researcher also gave assurance to the participants that no one, not even the researcher would be able to link data to a specific individual. In order to protect the anonymity of research participants, no names of mothers, or children are given.

Limitations of the Study

A limitation of the study is only rural areas were selected and data were collected from only two areas of Faridpur district. Another limitation of the study was the limited sample size and also the time duration is short. While conducting the study, the researcher faced some challenges in conducting IDIs keeping in mind the pandemic situation.

This chapter is designed to present the data which are collected from two different villages in the Faridpur district, Bangladesh. The data were collected from mid-October to the end of October 2021. A total of 40 adolescent mothers participated in the study. 20 mothers attended 20 IDI and 20 mothers attended 4 informal group discussions (5 members in each group). 2 pilot testing was done before starting the actual data collection. This chapter has two sections. One section consists of 3 different themes with sub-themes and another section is holding the key findings which are derived from the results.

Demographic profile of mothers and children

The age range of the mothers is 15-18 which indicates that all mothers are adolescent mothers. 20 mothers are from Sadarpur, which is the village of Bhanga Upazilla of Faridpur District. Another 20 mothers are from Shobharampur, which is the village of Sadar Upazilla in Faridpur District. All mothers have children between 0-3 years old. 24 of those children are female and 16 are male. 27 of the mothers are from a lower-income socio-economic background and 13 of them are from a lower middle-income socio-economic background. 4 of the mothers have completed their SSC examination, another 3 have passed 9th grade and the rest of the mothers completed only primary education. Except one all of the mothers are housewives. Only 2 of them live in a nuclear family and the rest of the mothers live in a joint family Table 1.

| Table 1: Demography. | ||

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

| Age | ||

| Less than 15 | None | 0% |

| More than 15 | 40 | 100% |

| Educational Level | ||

| Under Primary Education | None | 0% |

| Primary Education | 33 | 83% |

| Higher Secondary Education | 7 | 17% |

| Over Higher Secondary Education | None | 0% |

| Mother’s Employment Status | ||

| Employed | 1 | 2% |

| Unemployed | 39 | 98% |

| Socio Economical Class | ||

| Lower Income | 27 | 68% |

| Lower Middle Income | 13 | 32% |

| Child’s Gender | ||

| Male | 16 | 40% |

| Female | 24 | 60% |

Theme 1: Mothers’ perception of nutrition

Mothers’ understanding of nutrition: Most of the mothers have little knowledge about nutrition. Though all the mothers are familiar with the term nutrition but do not hold that much knowledge about it. Mothers who have an education background above 8th grade have little more knowledge than the mothers who only completed their grade 5th education.

‘I have heard the word nutrition from television and from people, saying about it. This is what I know about it. (IDI-1, 20.10.2021)

‘Do you mean ‘pushtikona’ (a supplementary, given by a non-profit organization)? From Brac apa (community health worker from BRAC) I have heard things like pushti (nutrition), pushtikona (supplement)’. (Group Discussion-2, Mother B, 25.10.2021)

‘Yes I’ve heard about nutrition and also we learned about it in our textbook. The body needs nutrition. A good amount of food and good quality food is needed to ensure nutrition. (IDI-5, 22.10.2021)

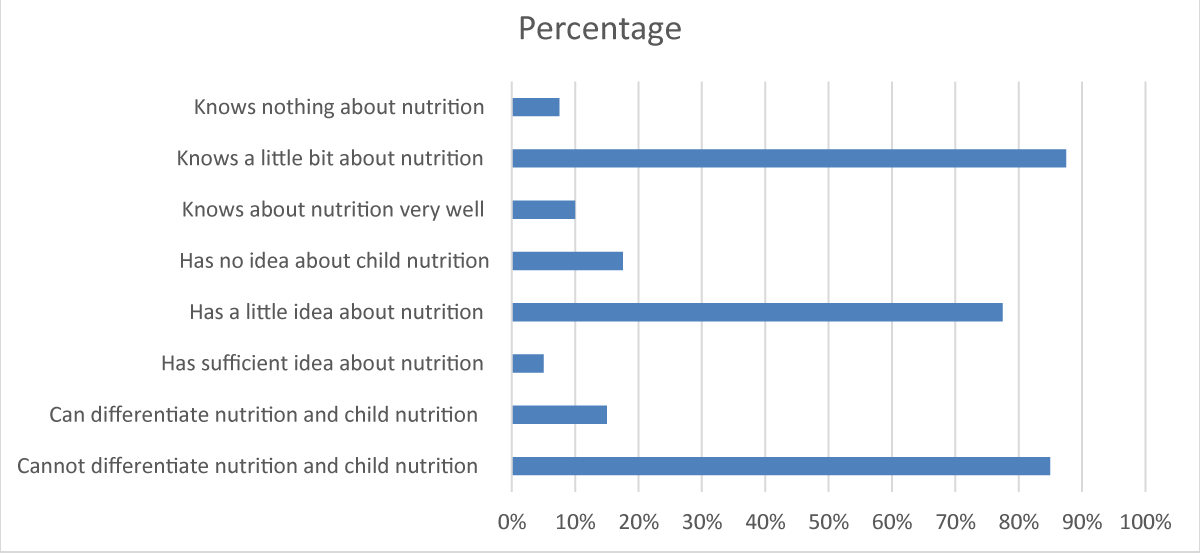

Mothers’ understanding of child nutrition: Most of the mothers have very little knowledge of child nutrition and to most of them the words ‘nutrition’ & ‘child nutrition’ are the same. They do not perceive the idea that ‘nutrition’ and ‘child nutrition’ are different words or different concepts Figure 1.

Figure 1: Mother’s perception of nutrition and child nutrition.

‘I try to give my child eggs, cow milk, and meat. Is it child nutrition?’ (IDI-1, 20.10.2021)

‘I give my child breast milk every day that is child nutrition to me’. (IDI-2, 20.10. 2021)

‘I’ve heard the word child nutrition but I do not know what it is’. (IDI-4, 21.10.2021)

‘Feeding them (children) what is good for them and feeding them timely is child nutrition’. (Group Discussion-2, Mother A, 25.10.2021).

Theme 2: Mother’s perception of child feeding

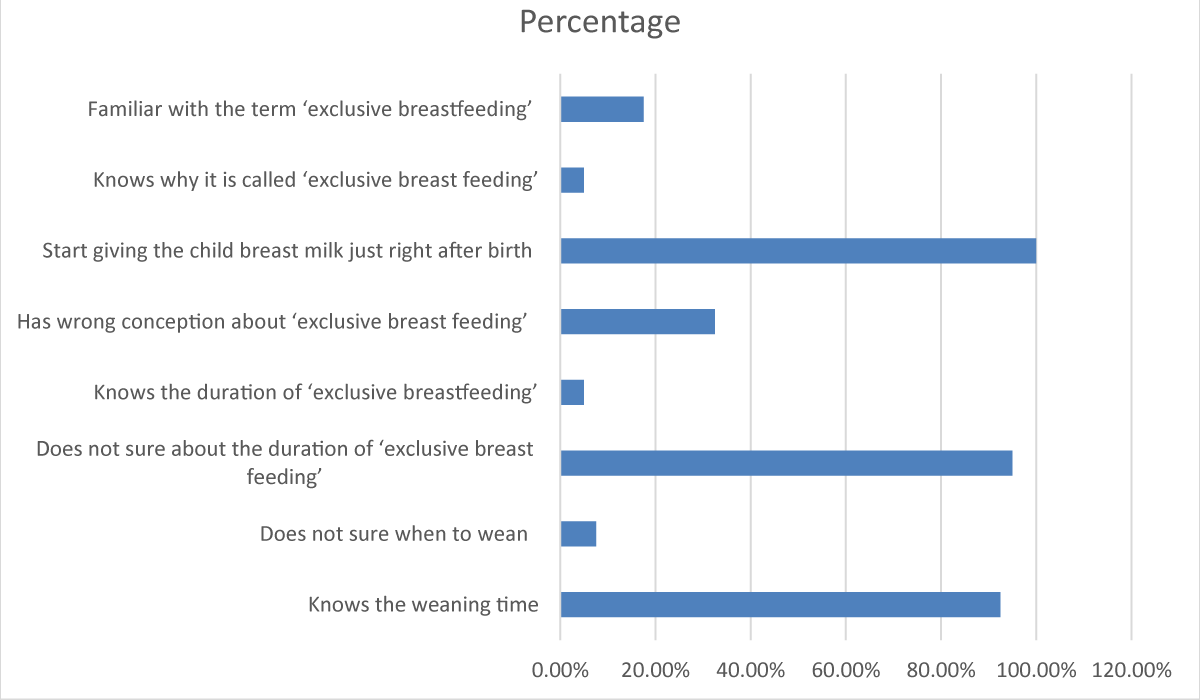

Mothers’ knowledge about exclusive breastfeeding and its importance: All mothers mentioned that breast milk is good for babies. All the mothers know the timeframe of exclusive breastfeeding which is up to 6 months. They also shared that breastfeeding should be started right after birth. All of them know that breastfeeding is important but they are unsure about the reason. When they were asked, what does that ‘exclusive’ word mean and why they think ‘exclusive breastfeeding’ is important they could not give the proper answer Figure 2A.

Figure 2A: Mother’s perception of exclusive breast feeding.

“Our elder family members like my mother, my mother-in-law always told me to breastfeed my child frequently. From them, I have heard that breast milk is so important. Then from the television advertisement I also heard it. When I was pregnant, I visited a doctor apa (lady doctor), and she also said breastfeeding is important.” (Group Discussion-1; Mother-C, 25.10.2021)

‘My child did not get sufficient breast milk. But I knew it was important so I tried hard to feed her breast milk.’ (IDI-6, 22.10.2021)

‘We heard from our elder, doctor and also when BRAC apa (community health worker from BRAC) came to visit she used to tell us to breastfeed our children. I know it is important but why, I cannot tell. To be honest, I never thought about it.’ (IDI-1, 20.10.2021)

‘Newborn baby needs to breastfeed with the right nutrition, I know that and I have done the same. I fed my child just after birth which we call ‘shaldudh’(very first breast milk) locally.’ (IDI-5, 22.10.2021)

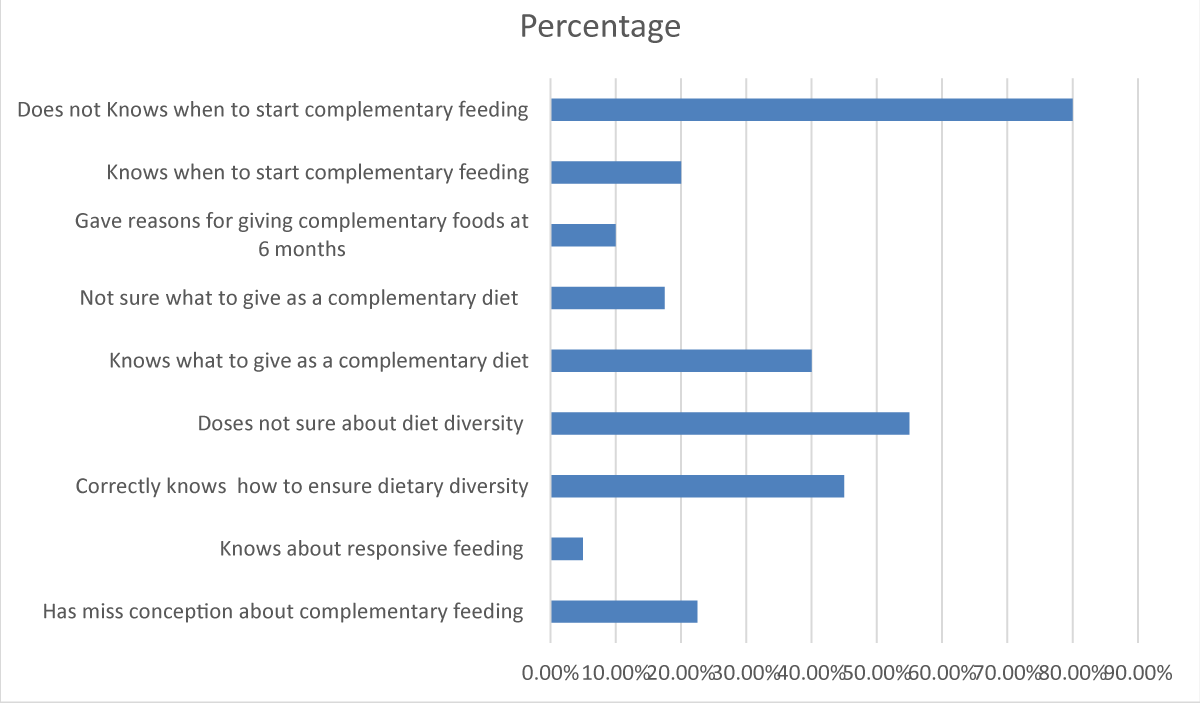

Mothers’ knowledge about complementary feeding & it’s importance: The majority of mothers understand that their child needs to be introduced to solid food or family foods from the age of 6 months besides breastfeeding. All mothers know that after 6 months breast milk alone is not sufficient for child growth. The majority of participants know that the ideal time to start feeding solid family foods is at 6 months of age and they also gave complementary food after 6 months. But some of them reported that they tried to feed their child solid food at the age of 4 months old. Because they think fruit is an essential food for a baby’s growth Figure 2B.

Figure 2B: Mother’s perception of complementary feeding.

‘She (child) does not eat properly. I try to give them ‘khichuri’(a dish typically made of rice, lentils, and different vegetables) but she does not eat it. I try to breastfeed but she also does not always drink. I give her ‘bhaat’er mar’ (rice water) sometimes but I try to give her soft fruit and fruit juice (freshly squeezed) every day because she likes it and I think fruit is important for my child’s healthy growth.’ (IDI-4, 21.10.2021)

When they were asked if they think complementary food is important, all of them mentioned that it’s important for child growth. Some of them also mentioned that good complementary food is a determiner of good health. When mothers were asked which complementary foods they think are best for their little children, different types of foods were mentioned. Rice is seen as a great complementary food because most mothers think it gives their child energy and grows their children fast. Some mothers think that vegetables are best since they are full of vitamins. Some mothers also mention that pure cow milk is a good complementary food to them. Some mothers mentioned that fruits are important to them for the healthy growth of their children.

‘Cow milk has so many vitamins. For a child, nothing is better than pure cow milk. I feed my child cow milk every day and make different food items like ‘Shuji’ (semolina) with cow milk to feed my child.’ (Group Discussion-1; Mother C, 25.10.2021)

‘I have tried to give my child ‘anarer rosh’ (pomegranate juice) at least once a week when I first started to give him complementary foods. Fruit juice is so important to me. I cannot buy expensive fruit every day but I try to manage.’ (Group Discussion-1; Mother A, 25.10.2021)

Theme 3: Mother’s practices on feeding

Practices on exclusive breastfeeding and its duration: All mothers in this study reported that they breastfed their child just right after the birth. Majority of the mothers know that breastfeeding is sufficient alone for a baby for the first 6 months of life. So they do not try gave/give any solid other food besides breastfeeding. But some mothers reported that they gave solid food before 6 months because one of them, despite knowing that fact she had to give her child other food, had very few amounts of breast milk which is actually insufficient. Another mother started giving solid food from the age of 4 months.

‘No no! I did not give any solid food before 6 months. One apa came to visit our area when my child was 1 month old, she told us not to give any solid food before 6 months. (Group Discussion-2, Mother B, 25.10.2021)

‘My child did not get sufficient breast milk. So she used to cry. First 3 months I gave her ‘lactogen milk’. But that was too expensive. So I started giving solid foods before reaching 6 months.’ (IDI-6, 22.10.2021)

‘I started giving her ‘khichuri’ at 4 months. I give her ‘kichuri’ with ‘shining macher jhol’. She liked to eat it. Sometimes I also gave her mashed potatoes.’ (IDI-4, 21.102021)

But the scenario for liquid foods such as water, and juice is a little different. Most of the mothers reported that they gave liquid food to their children before reaching 6 months of age. Mothers think their child needs water besides breast milk.

‘I gave water besides breast milk. We all need water, especially when my child was born, it was summertime then. We all get thirsty in summer so the baby must also feel the thirst, that’s why I gave water.’ (IDI-1, 20.10.2021)

‘I gave her freshly squeezed fruit juice. I have heard that fruit is an important food for child growth so I gave her fruit juice besides breast milk when she was 4 months old.’ (IDI-4, 21.10.2021)

As the study area was a Muslim-inhabited area and all the participants of this study were Muslim, so they all stated that the duration of breastfeeding will be 2-2.5 years as according to Islamic law mothers are allowed to breastfeed their children for 2 years. They said that they will be continuing breastfeeding for 2 years or a maximum of 2.5 years.

Practice complementary feeding: The majority of mothers reported that they have introduced complementary feeding to their children at the age of six months. The most commonly reported complementary food was ‘khichuri’, boiled soft rice, vegetables (mostly potato, papaya, and spinach), soft fruit or fruit juice, and eggs. Every mother in this study believes in responsive feeding. This behavior or feeding pattern from rural adolescent mothers is really admirable. All of them agreed on one point that force-feeding is not a good practice. They never force their child and sometimes wait to let their child call for food or sometimes they try to figure out different ways to feed their child.

‘If my child does not want to eat, I asked her father to bring something she likes to eat. Then I tell her to finish the ‘rice’ then I will give you this chocolate/chips.’ (Group discussion-1; Mother B, 25.10.2021)

‘If my child does not want to eat, I wait for the call. When he calls for food I feed him. I never force my child to eat.’ (IDI-6, 22.10.2021).

None of them mentioned any fixed timetable or fixed amount of meal. Almost all mothers reported the same pattern of meal frequency. They said they usually try to feed solid food 3 to 4 times a day. But if the child still remains hungry or wants to eat they feed them accordingly. Even they stated the same thing about breastfeeding. They said they maintain no timetable. When they feel their child needs to feed they feed. And one important thing is they mentioned that at night time they only feed breast milk, no bottled milk or anything because feeding breast milk at night is convenient.

‘Making a milk bottle at midnight is trouble so I just give my child breast milk if my child cries at night.’ (Group Discussion-1; Mother-A, 25.10.2021)

Mothers from low-middle-income families tend to design complementary feeding with diverse food items or recipes. But mothers from lower-income families are not always able to do that and also they have apathy to design a diversified diet. Mothers from lower-income families in this study told almost the same thing regarding meal diversification. They said if the child does not want to eat eggs regularly, they give them vegetables, if they get bored with vegetables, they just feed them rice mixed with cow milk. But they do not mention trying different recipes of the same food item, like egg curry, egg with vegetables, egg custard, and these kinds of variations.

Some of them who are from lower-income families also mentioned that they know a child needs to feed eggs, poultry, or fish regularly. Children need a different variety of vegetables but they cannot provide these food items every day because of a lack of affordability. On the other hand, one mother in this study has affordability but due to the lack of proper knowledge she does not provide her child exactly what the child needs, rather she feeds her child what seems like good food to her Table 2.

| Table 2: Correlation of mother’s demography and mother’s practice on exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding. | ||||||

| Variables | Exclusive Breastfeeding | Adequate amount of complementary feeding | Force Feeding | |||

| Yes (8) | No (32) | Yes (4) | No (36) | |||

| Yes (13) | No (27) | |||||

| The child’s mother has completed primary education (33) | 9% (3) | 91% (30) | 27% (9) | 73% (24) | 9% (3) | 91% (30) |

| The child’s mother has completed secondary education (7) | 72% (5) | 28% (2) | 57% (4) | 43% (3) | 14% (1) | 86% (6) |

| The Child’s mother is unemployed (39) | 21% (8) | 79% (31) | 30% (12) | 70% (27) | 10% (4) | 90% (35) |

| The Child’s mother is employed (1) | 0% (0) | 100% (1) | 100% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 100% (1) |

| Lower Income socio background ( 27) | 26% (7) | 74% (20) | 15% (4) | 85% (23) | 4% (1) | 96% (26) |

| Lower Middle-Income socio background (13) | 8% (1) | 92% (12) | 69% (9) | 31% (4) | 23% (3) | 77% (10) |

| Male Child (24) | 21% (5) | 79% (19) | 33% (8) | 77% (16) | 8% (2) | 92% (22) |

| Female Child (16) | 19% (3) | 81% (13) | 31% (5) | 79% (11) | 12.5% (2) | 87.5% (14) |

‘As she (child) loves to ‘shing macher jhol’ (fish curry) so I try to give her ‘shing macher jhol’ (fish curry) every day. And I try to feed her rice every day.’ (IDI-4, 21.10.2021). Some mothers are still holding superstitions about child feeding. They shared some impractical thoughts about feeding and child growth. One of the mothers mentioned the term ‘ola banga’ (an unpopular term used as a superstition).

“My mother-in-law said if I do not feed my child pure cow milk, my child will not grow taller and active because it will keep him down from ‘ola bhanga’ (an unpopular term used as a superstition). So I gave my child cow milk beside breast milk from 2 or 3 months.” (Group Discussion-1; Mother C, 25.10.20210)

Key findings

- All the mothers agree that child feeding is an important issue. No matter how much work they have, they do not avoid their child when it’s time to feed.

- Mothers from both lower-income and lower-middle-income socio-economic backgrounds know very little about nutrition. They are familiar with the terminology but they do not know the details of it.

- Mothers who completed only their primary education (grade V) have less idea about nutrition and proper feeding than the mothers who finished their 9th grade and who passed their SSC examination.

- There is no gender discrimination is reported in feeding practices.

- All mothers are aware of exclusive breastfeeding. But in reality, they sometimes misinterpret the term and use water and/or other liquid foods. They know it is important but the reasons are still unclear to them.

- All mothers have a satisfactory level of knowledge about breastfeeding frequency, duration, and cessation. But the practices sometimes differ from the expectations due to many challenges they face, such as insufficient breast milk, extreme heat during summer days water is given with breast milk, and mothers think cow milk is better for a baby's growth.

- Mothers have limited knowledge about complementary foods. Almost every one of them (except 1 mother) knows when to start complementary foods but they are not aware of what to feed as well as what is appropriate for their child. They just made a good food model according to them which is mostly rice or cow milk.

- Mothers from lower-income families cannot afford the proper complimentary meal for their children due to financial hardship. Mothers from lower-middle-income families have the ability to provide a proper meal but sometimes they do not serve a proper meal due to lack of knowledge. Despite having affordability some mothers still do not give what their child needs every day rather than they give what their child loves to eat.

- Usually, mothers from lower socio-economic backgrounds are unable to diversify the meals of their children. Mothers from lower-middle-income families and mothers who are more educated academically tend to alter the meal of their children.

- Mothers who are less educated are practicing more problematic feeding patterns than mothers who are a little more educated.

- Still, few less educated rural mothers hold some superstitions about child feeding.

- Almost all mothers do not believe in force-feeding. Though they reported this situation as frustrating, all of them have the same thought that a child should not be forced into feeding. They usually try to figure out different ways to feed their child.

The study population has a different demographic profile. Some of them are from lower middle income families and some of them are from lower income socio-economic status. Their academic education level is different also. Some of them just have primary education or less than it. On the other hand, this study also has mothers who went to high school and who have passed secondary education. These results highlight what are the perceptions of adolescent mothers on nutrition and feeding practices, and what practices they do in order to feed their children. As mothers are the primary caregiver in most families and usually mothers cook and provide food so this study targeted only mothers as the point of interview.

The major analysis of this study revealed the perception of how mothers define ‘Nutrition’ and ‘Child Feeding’. It is found that mothers who have less education know very little about nutrition, and child feeding, and have more misconceptions, and mothers who have a little more education have better knowledge about nutrition and child feeding compared to the previous group. The significance of a mother’s education for a child’s well-being and nutrition has been well demonstrated and numerous researches have revealed that maternal education influences children’s health and nutritional outcomes [22-25] stated that maternal education influences children’s health and nutritional outcomes. There is a retrograde relationship between knowledge and affordability found in some mothers. Two mothers reported that they are not able to buy nutritious food every day because of affordability although they answered roughly right about complementary food. And also, some mothers who have affordability do not have sufficient knowledge about child feeding because of the lack of education. According to the United Nations Second Report on the world nutrition situation (1992), the practices and attitudes of people are impacted by knowledge, awareness, and aptitude levels. Indeed in families with similar levels of access to expendable wages and assets, there’s a wide variety in nutritional results of children. It is clear that if mothers have affordability still there is a chance that their child will not get proper nutrition because those mothers have knowledge gaps which will reflect on their practices. All mothers are aware of exclusive breastfeeding recommendations for the first 6 months, but they do not know what means ‘exclusive’ and why it is important, also unknown to them, and some of them interpret ‘exclusive’ to mean breast milk and liquids foods like water or pure cow milk. But some of the mothers again think breast milk is sufficient for the first 6 months. According to some researchers they have also found a similar kind of scenario in adolescent girls. They mentioned they have found that adolescent girls are aware of IYCF’s recommendation to breastfeed only for 6 months but they interpret ‘exclusive’ to breast milk and other fluids [26]. These findings together, propose that misinterpretations of the ‘exclusive breastfeeding’ idea stay common in different areas of Bangladesh and may be similar in different rural populations. Almost all mothers reported that they have started breastfeeding right after birth. Every one of them said that they will be continuing breastfeeding for up to 2-2.5 years. Most of them agreed that no solid food is needed in the first 6 months of age. Water is mostly reported as non-breast milk fluid encouraged to infants before 6 months. In terms of perceptions of breast milk and newborn baby’s thirst, even in hot areas and hot seasons, according to WHO [7], healthy newborn children do not need additional water during their first 6 months of age while they are exclusively breastfed. Breast milk is composed of 88% water, which is enough to satisfy a baby’s thirst. Few mothers mentioned that they give cow milk, freshly squeezed homemade fruit juice, and nutritious drinks to their babies. According to Dykes & Williams [27] breast milk insufficiency can be taken as a reason not to breastfeed or it can also even become a fact because of not frequent suckling, because suckling is the stimuli required for continued production of breast milk.

The majority of mothers know that the ideal time to start giving solid family foods is at 6 months of age. They are also practicing this in their regular life as most of them shared that they were introduced to solid food at the age of 6 months of their child. But a few mothers also tend to introduce complementary food earlier because of knowledge gaps and some misconceptions in them about feeding practices and another reason behind this is insufficient breast milk. Mothers who mostly misinterpret the IYCF guidelines are found less educated. Their less education creates a knowledge gap which leads to misconceptions and misinterpretations.

One important thing that has been found from this study is that mothers of today’s generation are not likely to discriminate against girl children, especially with regard to food quality and the amount of complementary foods. According to USAID (2021), in gender equality, Bangladesh has made noteworthy prosperity in the last 20 years. The previous scenario of gender-biased attitude has changed a lot. This remarkable change suggests that today’s mothers, as well as family members, hold a positive attitude toward female children. All the mothers mentioned that there is no fixed time that they follow to breastfeed, when they feel the baby needs it, they feed them according to their baby’s demand or whenever they cry. Different mothers have different kinds of breastfeeding frequencies. Perceptions and practice about the timing of the introduction of complementary food are pretty satisfactory. Almost all mothers agreed that solid food needs to be given after the age of 6 months. Though they have a misconception about giving other liquid (water, fruit juice) before 6 months but in terms of giving solid food just a few mothers said that they tried/try to give ‘kichuri’ ( a dish typically made of rice, lentils and different kind of vegetables) or a very little portion of plain rice to their child before 6 months. When mothers were asked which complementary foods are ideal and best for their children, different mothers respond in a different way. One of them strongly believes that cow milk is the best food. One of them says fruit is very nutritious and fruit needs to be given every day. But the most commonly believed concept among mothers is that rice is a great food, a source of energy and rice helps a child to grow. So they cook ‘khichuri’ (a dish typically made of rice, lentils, and different kind of vegetables) with a combination of ‘chal’ (rice) and ‘dal’ (lentils). The comparable result has been also found in two other studies done in a rural community in Bangladesh and in a slum of Dhaka city [28,29]. Those studies found that ‘khichuri’ (a dish typically made of rice, lentils, and different kind of vegetables) was the most reported complimentary food in the rural region of Bangladesh and another commonly believed good food was eggs [30]. No fixed meal timing was reported by mothers. Every mother’s answer was almost the same at this point. They try to serve food at least 3 times a day. Besides, they also serve food to their children on demand. They also reported that, if a baby cries, they give them food to keep them quiet. Another thing they mentioned is that when family members sit to eat, sometimes their child wants to eat with them, that time they give small portions of food into their mouth. Diversity of meals found in financially stable families. Mothers who are from a lower middle-income family can manage to offer a variety of foods to their children, on the other hand, meal diversifying practice is very low in mothers who are from lower-income families. The major reason behind not being encouraged to eat a suitable amount according to age and not being fed from different food groups are reported to be insufficient knowledge, a child’s unwillingness to eat and not being able to manage enough food. Mother’s lack of knowledge is responsible for their perceptions and their knowledge gaps reflect in their practices. Other than the mother’s affordability is another reason for improper feeding.

Young mothers are found way better at practicing responsive feeding. Mothers in this study don’t believe in force-feeding. Different studies on human behavioral issues observed that responsive feeding with psycho-social care practices incorporates a positive impact on child development and improvement [31,32]. Mothers in this study reported that they try to figure out different ways to feed their children. In another study, they found that the practices of giving minimum meal frequency and the least amount of food were better than other practices of mothers. And researchers of that study said that it could be due to responsive feeding given to the child whenever the child cried [33]. From this study, we can see that responsive feeding practice is also common in lower-class mothers.

There are some barriers, which lead to the malpractice of child feeding. Two common barriers found in the study are, (1) Insufficient breast milk and (2) Unaffordability. For insufficient breast milk, mothers give other liquids such as lactogenic milk, fruit juice, and ‘bhat er mar’ (rice water) to their children. In lower-income families, the big deal is their ability to afford good-quality food items. This study has found some mothers have a minimum knowledge of complementary feeding but due to their unaffordability, they cannot serve all food that their child needs on a regular basis. They just simply feed their child whatever is available at home. Another finding of this study is that diet diversity is more common in lower middle-income families than lower-income families. Families who do not have affordability are more apathetic in designing diverse meals for their children. A major misconception lies in ‘exclusive breastfeeding’. Mothers take this ‘exclusive’ as no solid food during the first 6 months of age but other liquid food can be given besides breastfeeding. Water is very common to those mothers. They think water is a must-have thing in daily life. Another misconception is, to the mothers crying is an indication of the child is hungry or the breast milk or food is insufficient so they offer breast milk or food whenever the child cries. Babies crying do not always indicate that they are hungry but their mothers misinterpret the signal most often. Every mother has her own concept of ‘good complementary food’. Concepts of ‘good food’ of more educated mothers are better than less educated ones, The mothers who have less education and less knowledge about nutrition and child feeding have made mistakes in giving the definition of good food. Some of those mothers mentioned cow milk is the best, some of them mentioned vegetables but the most commonly reported ‘good food’ is rice. Very few mothers have knowledge of a properly balanced diet other than that rest of mothers’ ‘good food’ concept depends on any one food item (like only rice, only vegetable, only egg or cow milk), and whatever they serve to their child this one ‘good food’ is a must-have item.

Newborn child and young child feeding practices could be a key area to improve child development areas and promote sound growth and improvement. The primary years of a child’s life are immensely vital, as ideal nutrition amid this period brings down morbidity and mortality, diminishes the chance of persistent illness, and cultivates better advancement in general. The result of this study has explored particular knowledge gaps of rural adolescent mothers in nutrition and child feeding. This gap could be addressed by focusing on interventions for adolescent mothers in rural Bangladesh. Adolescent mothers need education and knowledge to influence the opportunity of positive impact on newborn child wellbeing results. An expanded venture in the early education of young adolescents to establish a secure IYCF practice could be a viable technique to advance and support improved and advanced child feeding practices. If social and financial strength, as well as knowledge on child feeding, could be imparted to adolescent mothers, there might be a chance that these interventions will play a vital role in the creation of more advantageous and healthier communities all throughout Bangladesh.

Widespread take-up of international IYCF recommendations will be troublesome to attain without knowing the regular practices, and daily life experiences of needy primary caregivers inside particular communities. Documenting adolescent mothers’ knowledge, demeanors and perceptions, and practice on infant and child feeding is an imperative research need since mothers are likely to influence feeding practices as they are the primary caregiver.

- Chen LC, Chowdhury A, Huffman SL. Anthropometric assessment of energy-protein malnutrition and subsequent risk of mortality among preschool aged children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980 Aug;33(8):1836-45. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.8.1836. PMID: 6773410.

- Bardosono S, Sastroamidjojo S, Lukito W. Determinants of child malnutrition during the 1999 economic crisis in selected poor areas of Indonesia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16(3):512-26. PMID: 17704034.

- Khanal V, Sauer K, Zhao Y. Determinants of complementary feeding practices among Nepalese children aged 6-23 months: findings from Demographic and Health Survey 2011. BMC Pediatr. 2013 Aug 28;13:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-131. PMID: 23981670; PMCID: PMC3766108.

- Dibley MJ, Roy SK, Senarath U, Patel A, Tiwari K, Agho KE, Mihrshahi S; South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network. Across-country comparisons of selected infant and young child feeding indicators and associated factors in four South Asian countries. Food Nutr Bull. 2010 Jun;31(2):366-75. doi: 10.1177/156482651003100224. PMID: 20707239.

- Kabir I, Khanam M, Agho KE, Mihrshahi S, Dibley MJ, Roy SK. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in infant and young children in Bangladesh: secondary data analysis of Demographic Health Survey 2007. Matern Child Nutr. 2012 Jan;8 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):11-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00379.x. PMID: 22168516; PMCID: PMC6860519.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2009) Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals. WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2009). Global Data Bank on Infant and Young Child Feeding. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44117/9789241597494_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Saizuddin M, Hasan MS. Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Practices by Rural Mothers of Bangladesh. Journal of National Institute of Neurosciences Bangladesh. 2017; 2(1): 19-25.

- Huq KO, Haque N, Akther F. Comparison of the Nutritional Status and Infant Feeding Practices Between Selected Rural and Urban Areas in Bangladesh. Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2017; 5(5): 167.

- Gyampoh S, Otoo GE, Aryeetey RN. Child feeding knowledge and practices among women participating in growth monitoring and promotion in Accra, Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 May 29;14:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-180. PMID: 24886576; PMCID: PMC4047542.

- Egata G, Berhane Y, Worku A. Predictors of non-exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months among rural mothers in east Ethiopia: a community-based analytical cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2013 Aug 7;8(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-8-8. PMID: 23919800; PMCID: PMC3750393.

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia]. ICF International. Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa and Calverton: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International. 2012. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr255-dhs-final-reports.cfm

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Bangladesh. Infant and young child feeding. 2020. Retrieved from, https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/sites/unicef.org.bangladesh/files/2018-10/Guidelines%20for%20CF.pdf

- Eneroth H, El Arifeen S, Persson LA, Kabir I, Lönnerdal B, Hossain MB, Ekström EC. Duration of exclusive breast-feeding and infant iron and zinc status in rural Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2009 Aug;139(8):1562-7. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104919. Epub 2009 Jun 17. PMID: 19535419.

- Giashuddin MS, Kabir M. Duration of breast-feeding in Bangladesh. Indian J Med Res. 2004 Jun;119(6):267-72. PMID: 15243164.

- Huffman SL, Chowdhury A, Chakraborty J, Simpson NK. Breast-feeding patterns in rural Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980 Jan;33(1):144-54. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.1.144. PMID: 7355776.

- Rasheed S, Haider R, Hassan N, Pachón H, Islam S, Jalal CS, Sanghvi TG. Why does nutrition deteriorate rapidly among children under 2 years of age? Using qualitative methods to understand community perspectives on complementary feeding practices in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2011 Sep;32(3):192-200. doi: 10.1177/156482651103200302. PMID: 22073792.

- Haider R, Kabir I, Hamadani JD, Habte D. Reasons for failure of breast-feeding counselling: mothers' perspectives in Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75(3):191-6. PMID: 9277005; PMCID: PMC2486944.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Pregnant Adolescents: Delivering on Global Promises of Hope. 2006. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43368

- Haggarty L. What is content analysis? Medical Teacher. 1996; 18(2): 99–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research

in Psychology. 2006; 3(2): 77–101. - Caldwell JC. Education as a Factor in Mortality Decline: An Examination of Nigerian Data. Population Studies. 1979; 33(3): 395-413.

- Kabubo-Mariara J, Ndenge DK. Determinants of Children's Nutritional Status in Kenya: Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. Journal of African Economies. 2009; 18(3): 363–87.

- Ruel MT, Habicht JP, Pinstrup-Andersen P, Gröhn Y. The mediating effect of maternal nutrition knowledge on the association between maternal schooling and child nutritional status in Lesotho. Am J Epidemiol. 1992 Apr 15;135(8):904-14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116386. PMID: 1585903.

- Mosley WH, Chen LC. An Analytical Framework for the Study of Child Survival in Developing Countries. Population and Development Review. 1984; 10(Supplement): 25–45.

- Hackett KM, Mukta US, Jalal CS, Sellen DW. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions on infant and young child nutrition and feeding among adolescent girls and young mothers in rural Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr. 2015 Apr;11(2):173-89. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12007. Epub 2012 Oct 15. PMID: 23061427; PMCID: PMC6860341.

- Dykes F, Williams C. Falling by the wayside: a phenomenological exploration of perceived breast-milk inadequacy in lactating women. Midwifery. 1999 Dec;15(4):232-46. doi: 10.1054/midw.1999.0185. PMID: 11216257.

- Islam MZ, Farjana S, Masud JHB. Complementary feeding practices among the

mothers of a rural community. Northern International Medical College Journal. 2012; 3(2):

204-207. - Akhtar K, Hoque ME, Islam MZ, Yusuf MA, Sharif AR, Ahsan AI. Feeding

Pattern and Nutritional Status of Under Two Years Slum Children. J Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College. 2012; 4(1): 3-6. - Karim M, Farah S, Jannat FJ. Study on feeding practices of infants among the

mothers in selected villages, at Dhamrai. J. Dhaka National Medical College Hospital. 2012;

18(02): 30-36. - Engle PL, Bentley M, Pelto G. The role of care in nutrition programmes: current research and a research agenda. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000 Feb;59(1):25-35. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000045. PMID: 10828171.

- Pelto GH, Levitt E, Thairu L. Improving feeding practices: current patterns, common constraints, and the design of interventions. Food Nutr Bull. 2003 Mar;24(1):45-82. doi: 10.1177/156482650302400104. PMID: 12664527.

- Pryer JA, Rogers S, Rahman A. The epidemiology of good nutritional status among children from a population with a high prevalence of malnutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2004 Apr;7(2):311-7. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003530. PMID: 15003139.

- Rahman MA, Khan MN, Akter S, Rahman A, Alam MM, Khan MA, Rahman MM. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice in Bangladesh: Evidence from nationally representative survey data. PLoS One. 2020 Jul 15;15(7):e0236080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236080. PMID: 32667942; PMCID: PMC7363092.